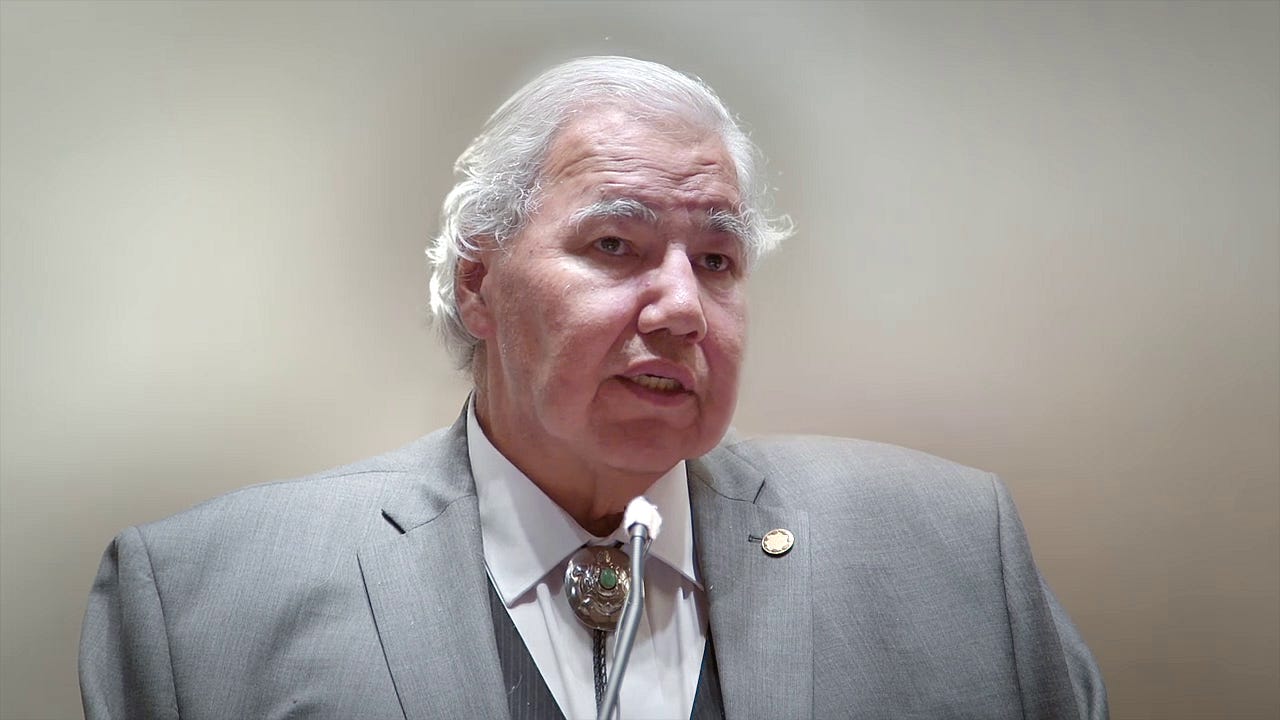

Murray Sinclair was a national treasure

Filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin captures the wisdom, kindness and determination of former senator Murray Sinclair in her 29-minute doc: Honour to Senator Murray Sinclair. Watch it!

Murray Sinclair, former Judge, Senator and Truth and Reconciliation Committee Chair Credit: National Film Board of Canada

I don’t usually publish on Tuesdays, but the passing of Calvin Murray Sinclair cannot be overlooked nor the loss to this country overstated.

No doubt some readers may think I’ve made a mistake with his name. Not so. In 2019 I attended an event featuring Murray Sinclair’s son Dr. Niigaan Sinclair. Niigaan told the audience that his father’s first name was Calvin, but when he attended residential school they insisted he use his middle name rather than his given name.

Today, I’m going to focus on the 2021 documentary Honour to Senator Murray Sinclair which made its world premiere at the 2021 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) as part of the Celebrating Alanis retrospective.

A member of the Abenaki Nation, Alanis Obomsawin is Canada’s most prolific and honest documentary-filmmaker and this work is nothing short of inspiring. Obomsawin shares the powerful speech made by the former senator and chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Murray Sinclair when he accepted the World Peace Award from the World Federalist Movement Canada in 2016.

Obomsawin artfully interspersed Sinclair’s talk with the heart-wrenching testimonies of Iris Nicolas, Victoria Crowchild, James Yellow Knee, Paul Voudrach, Ida Embry and Saul Day — all of whom were imprisoned at residential schools as children.

As the chair of the TRC, Sinclair was a key figure in raising global awareness of the atrocities meted out through Canada’s residential school system. The TRC grew out of the residential school settlement agreement. It was largely controlled by the Harper government, who insisted that only the term cultural genocide be included in the report.

Sinclair, Anishinaabe and a member of the Peguis First Nation, inherited a TRC in chaos. A year later, in 2010, the commission held its first national event in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Over 20,000 folks attended to bear witness to the traumas endured by residential school survivors.

Church and government leaders were encouraged to speak to their audiences providing the validity some Canadians needed in order to accept the horrific treatment Indigenous children endured.

In June 2015, the final report — including 94 Calls to Action — was released. According to Indigenous Watchdog, “The federal government is accountable for 76 of the 94 Calls to Action – either alone or in partnership with the provinces and territories. As of January 1, 2024, according to Indigenous Watchdog, 11 of those Calls to Action are COMPLETE and 39 are IN PROGRESS. That represents 66 per cent of the C2A!”

The site also states, “Of the 65 Calls to Action that the government claims are well under way – excluding the 11 that are complete – 26 Calls to Action or 40 per cent are either NOT STARTED or STALLED.”

Sinclair asked us to look to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) to create the framework for reconciliation. Adopted by 144 nations on September 13, 2007, Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand voted against UNDRIP.

While Canada endorsed UNDRIP in 2010, adoption only took place in May 2016 and UNDRIP is still not legally binding in Canada.

Sinclair pointed out that some of the rights upheld by UNDRIP already existed in Canada. These rights were established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which, among other things, prevented the government from declaring outright war on Indigenous nations. Instead, the Canadian government used legislation to wage its war.

Seven generations of stolen children were imprisoned in residential schools. Yet, Sinclair reminds us the public school system also had devastating effects on Indigenous children often treating them as “less than.” Curriculums continue to omit Indigenous contributions to the history of this country, cultivating an air of superiority in non-Indigenous children. As Sinclair sagely observed, reconciliation will take generations to achieve.

With determination, wisdom and kindness, Sinclair remained steadfast in his belief that the path to actual reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people requires understanding and acceptance of often difficult truths about Canada’s past and present.

Sinclair challenged Canadians to choose one Call to Action and make it happen. Now, that would be a fitting tribute to Murray Sinclair’s life, his work and his memory.

Honour to Senator Murray Sinclair reminds us to honour the lives and legacies of the tens of thousands of Indigenous children taken from their families, communities and cultures while leaving us with a profound feeling of hope for a better future.

Honour to Senator Murray Sinclair (2021; 29 minutes) is available free on the National Film Board (NFB) of Canada site.

A version of this article first appeared on rabble.ca.

Thanks to everyone who read today’s article. With your continued support, a little Nicoll can make a lot of change.

I attended the hearing held in Halifax when Murry Sinclair was moderating the telling of the individual stories and submitted a short piece on electric chair victimization that I had learned about occurred in a residential "school." I found this Small Change article interesting.

Thank you Doreen; you have given us more links to understand in greater depth.

The idea of demoralizing the indigenous population seemed to work.

At teachers college in 1960, a friend from Manitoulin Island and I were discussing how hard it was to come back to class after a two week break at home.

She said “my friends didn’t make it any easier for me. One of them said, ‘ You think you are better than us but you are just a dirty old drunken Indian like the rest of us.’ “