Wilfred Buck revives Indigenous knowledge

“We are in the process of remaking an age-old song . . . singing, dreaming, praying, talking into existence once again the knowledge of our people,” Wilfred Buck, Indigenous scientist.

The United Nations definition of genocide is simple and includes five basic elements:

Killing members of the group.

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group.

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.

Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

The definition contained in Article II of the Convention describes genocide as a crime committed with the intent to destroy a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, in whole or in part.

It does not include political groups or so called ‘cultural genocide.’

And, that is why Prime Minister Stephen Harper demanded the Truth and Reconciliation Commission use the term ‘cultural genocide’ rather than outright genocide, because Canada was five-for-five as far as the UN definition of genocide goes.

Yet, on closer examination, the destruction of a people’s culture is the destruction of those people as a whole because their language, traditions, customs, art and artifacts are what make them unique. Eradicating those sacred parts of their lives leaves future generations without guidance or a means of navigating life and that in effect is genocide.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was mandated to listen to survivors of the residential school system. as well as their families and communities. The goal was to understand the effects of a variety of abuses children between four and 16 years-of-age experienced and the inter-generational trauma that resulted from their time at residential school.

It was also to educate Canadians about the existance of residential schools, their mandate and how children suffered irreperable, life altering trauma at the hands of their so-called educators and care providers.

Harper restricted the commission from referring to anything other than cultural genocide in its final reports which included 94 Calls To Action.

The inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and Two-Spirit people (MMIWG2S) was not tethered by such colonial demands and was able to identify the intentional femicide of Indigenous women and girls that is part of Canada’s larger systemic institutionalized genocide of Indigenous peoples.

So-called ‘Canada’ was established and built on the genocide of Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island, but that is changing.

Wilfred Buck teaches about the stars from his travelling dome. Credit: National Film Board of Canada

Lisa Jackson and The National Film Board (NFB) of Canada have created a documentary that redefines Indigenous knowledge and teachings using the life and times of Elder, cosmology and astronomy expert, Wilfred Buck.

“We are in the process of remaking an age-old song . . . singing, dreaming, praying, talking into existence once again the knowledge of our people,” said Wilfred Buck.

Moving between the earth and stars, past and present, this hybrid feature documentary follows the extraordinary life of Buck, a charismatic and irreverent Cree Elder who overcame a harrowing — yet all too familiar — history of displacement, racism and addiction by reclaiming ancestral star knowledge and ceremony.

Buck is humble, profound, funny, authentic and a master storyteller. Narration taken from his autobiography, I Have Lived Four Lives, condenses the loss and desperate pain of his youth into powerful, Beat-like poetry.

After his community in The Pas, Northern Central Manitoba,was forcibly relocated to make way for a hydroelectric dam, Buck’s family lost everything.

Indigenous sacred sites were desecrated and matriarchal lineage lost as ceremony became outlawed. Communities and land-based ways of life were destroyed by white supremacy, racism and capitalism.

As a teen on his own, Buck descended into the darkness of the city streets, surviving as best he could, until he reconnected with Elders who put him on a path that transformed his world.

Driven by insatiable curiosity and instructed by dreams, Buck became a science educator and internationally respected star lore expert. His mission is sharing these life-changing teachings — as relevant and urgent today as ever — always guided by ceremony and anchored in the land.

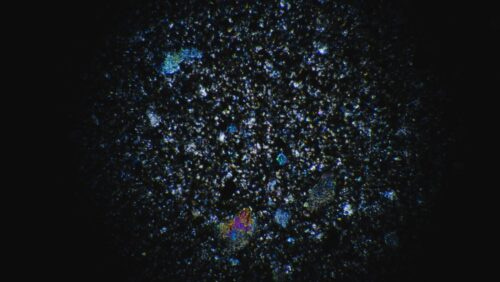

Martian Meteorite Credit: National Film Board of Canada

As the director, Jackson deftly interweaves verité footage of Buck’s present with archival footage and cinematic, dramatized scenes from his past, painting a portrait of a beloved leader who now stands at the forefront of the resurgence of Indigenous ways of knowing.

Buck, an Ininiw (Cree) astronomer, author, educator, addictions consultant, Knowledge Keeper and lecturer originally from Opaskwayak Cree Nation (OCN), graduated from the University of Manitoba with two degrees in education and has 25 years of experience as an educator, working with students from kindergarten to university.

Buck also worked as a science facilitator for 15 years at the Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre, where he did extensive research on Ininiw Acakosuk, also known as Cree stars/constellations, that were part of Turtle Island long before it was colonized and European constellations and interpretations were forced upon Buck’s people.

Currently, Buck gives presentations using his mobile planetarium, in addition to lectures and keynote presentations on Indigenous astronomy and Indigenous worldviews. He is considered the foremost authority on Indigenous astronomy in the world.

For Jackson, this documentary started with a sturgeon. In the summer of 2017 Jackson was reading an article when she saw the word “sturgeon” and experienced what she calls a zap — a bolt of fascination and urgency.

“I’ve learned to listen to them, as my most successful projects have started this way. I’d heard of this ancient fish before, but it had never had this effect on me. A seed was planted,” said Jackson.

Later that year, a friend asked Jackson to attend a panel on Indigenous star knowledge at the University of Toronto, and she went. When a man from the Canada Science and Technology Museum mentioned the name “Wilfred Buck,” she again felt that zap.

Weeks later when Buck and Jackson spoke by phone, Buck told her that he had just finished writing his life story and that no one knew he’d written it except his wife and daughter.

Later that day, Jackson read the first page of his memoir, I Have Lived Four Lives which stated: “I am Pawami niki titi cikiw, ‘He has Dreamed a Dream and Keeps it,’ shortened to ‘Dream Keeper.’”

It continued, “I am of the fresh-out-out-of-the-bush, partly civilized, colonized, displaced people. Trained and shamed by teachers, preachers, doctors, nurses, law enforcement, movie, radio and television to be a pill-popping, hard drinking, self-loathing, easily impressed, angry, non-conformist, maladjusted, disaffected youth of the “dirty-indian,” baby boomer generation. By all rights, I am told, I should be dead six times over.”

This is the story of colonialism of Indigenous people and their territory, but also of their mind and spirit told from an Indigenous perspective.

“Reading Wilfred’s words, I saw someone who’d been through the fire of what has broken countless Indigenous people, and survived. And who was now, with the help of his family and community, forging a path for others to heal and reconnect to the profound teachings of their ancestors through ceremony and star knowledge,” Jackson stated.

”I was riveted. Seamlessly moving from past to present, heartbreaking to hilarious, it was searingly honest, playful and wise. Here was a beat poet, born on the land, torn from it and thrown into a society that said his people were backwards, knew nothing, and that his ancestors were in Hell. Like many others, he fell into a deep hole of addictions, street life and pain, hurting others as he had been hurt,” she added.

The Sturgeon Credit: National Film Board of Canada

On the last page of Buck’s memoir was the story of Namew, the sturgeon. This Cree star constellation reminds Indigenous folks of their responsibilities to seven generations and beyond and that they are part of the continuity of knowledge through time, ensuring that the next generations have what they need to live a good life.

The sturgeon is a long-lived fish that swam with the dinosaurs. A fish that has endured extinction events. It swims low in rivers and lakes and carries lessons. Some say it can move between the worlds, above and below.

As a constellation, the sturgeon’s tale is the past, its nose is the future and where it swims is the present. Seven generations are held within that constellation.

“Colonization has taken a hatchet to the chain of knowledge our ancestors carried forward, but it didn’t sever it. And through the work of Wilfred and countless other Elders, knowledge keepers, teachers and oskapiwis (helpers), the knowledge is being transmitted again—no longer outlawed, ridiculed and diminished,” Jackson maintains.

Born to an Anishinaabe mother and a father of mixed European heritage, Jackson’s film conveys Ininew (Cree) teachings and Indigenous teachings about how to heal and how to come to new knowledge.

Jackson, and Buck, believe Indigenous knowledge is based on millennia-long observations of the Earth and skies that provided guidance on how to navigate and live in balance.

In a world drowning in data and information, folks are starved for wisdom and perspective. The film Wilfred Buck asks viewers to ponder the question: What is missing when there is no ceremony?

Jackson acknowledges that, ”Western knowledge and Indigenous knowledge have only just introduced themselves. And though there is a growing recognition of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, the mainstream categorization of rational thought and quantifiable data as completely separate from other ways of knowing is a barrier. There may be a willingness to listen, but there remains a gulf in language and worldviews. I hope this film can be an invitation for that dialogue to begin.”

Buck is the author of three books: Tipiskawi Kisik: Night Sky Star Stories (2018); the semi-autobiographical I Have Lived Four Lives (2021), on which Jackson’s documentary Wilfred Buck is based; and Kitcikisik (Great Sky): Tellings That Fill the Night Sky (2021).

Wilfred Buck (2024; 96 minutes) will be available on Crave in December. Find out more on the NFB site.

*A version of this article first appeared on rabble.ca.

Thanks to everyone who read today’s article. With your continued support, a little Nicoll can make a lot of change.

I have lived near and known Indigenous people all my early life. We have much to gain from Indigenous knowledge and we need to respect what they have endured and survived. The cruelest cut was demoralizing people to feel that they were “just dirty old Indians.”

The young men fought in WW 2 but when they returned, they were still denied the vote or the privilege of buying alcohol.

This education is very much needed.